Research from Goldsmiths University and Youthscape explores the place of religion, faith and spirituality on JNC-recognised youth work training courses across England.

Overview of the research

Youth workers in the UK are professionally qualified if they have a degree endorsed by the Joint Negotiating Committee for Youth and Community Work (JNC). Current National Occupational Standards (NOS) require youth workers to ‘Explore the concept of values and beliefs with young people’ (YW06) and ‘Develop a culture and ethos that promotes inclusion and values diversity’ (YW19), but there are no explicit references to religion, faith or spirituality.

Despite this, lots of youth workers work within or alongside faith organisations (which are the largest sector of the youth work field) and all youth workers need a level of ‘religious literacy’ (Dinham, 2018) if they are to beequipped to work sensitively and inclusively with diverse communities.

Dr Naomi Thompson and Dr Lucie Shuker conducted a survey with programme leaders and analysed programme webpages to explore what topics relating to religion, faith and spirituality are covered, in what context they feature (e.g. lectures, discussions or through fieldwork placements), and whether youth workers are being equipped to understand and work with diverse religious communities.

Participation in the research was high, with survey responses from 25 of the 27 institutions offering JNC-recognised qualifications in England, and 30 of the 38 courses on offer. Of the 25 institutions, 21 were mainstream universities, 3 were Christian-specialist providers, and one was a specialist college offering secular programmes.

What did we find?

Course leaders recognise that religion, faith and spirituality are important, but there is no consensus that NOS and the curricula of training programmes are sufficient to equip youth workers to work with diverse groups of young people around issues of religion, faith and spirituality.

- A minority of course leaders (37.9%) felt that the NOS (YW14) sufficiently represented the place of religion, faith and spirituality in youth work practice.

- Most course leaders we surveyed believed that youth workers should engage with issues of religion, faith and spirituality in their practice, either proactively (50%) or in response to issues raised by young people (23.3%).

- However, comments highlighted that this is complex, raising issues of power and its uses in youth work training – particularly where faith-based and secular values or practice are in tension.

- Two-fifths (40%) of course leaders are not confident or not sure that their graduates are sufficiently equipped to engage with young people from diverse religious and non-religious backgrounds on issues of religion, faith and spirituality.

“The programme team place a lot of emphasis on creating a safe environment for students to explore and be aware of self in relation to others. That said conversations about difference including discussion about faith can be uncomfortable.”

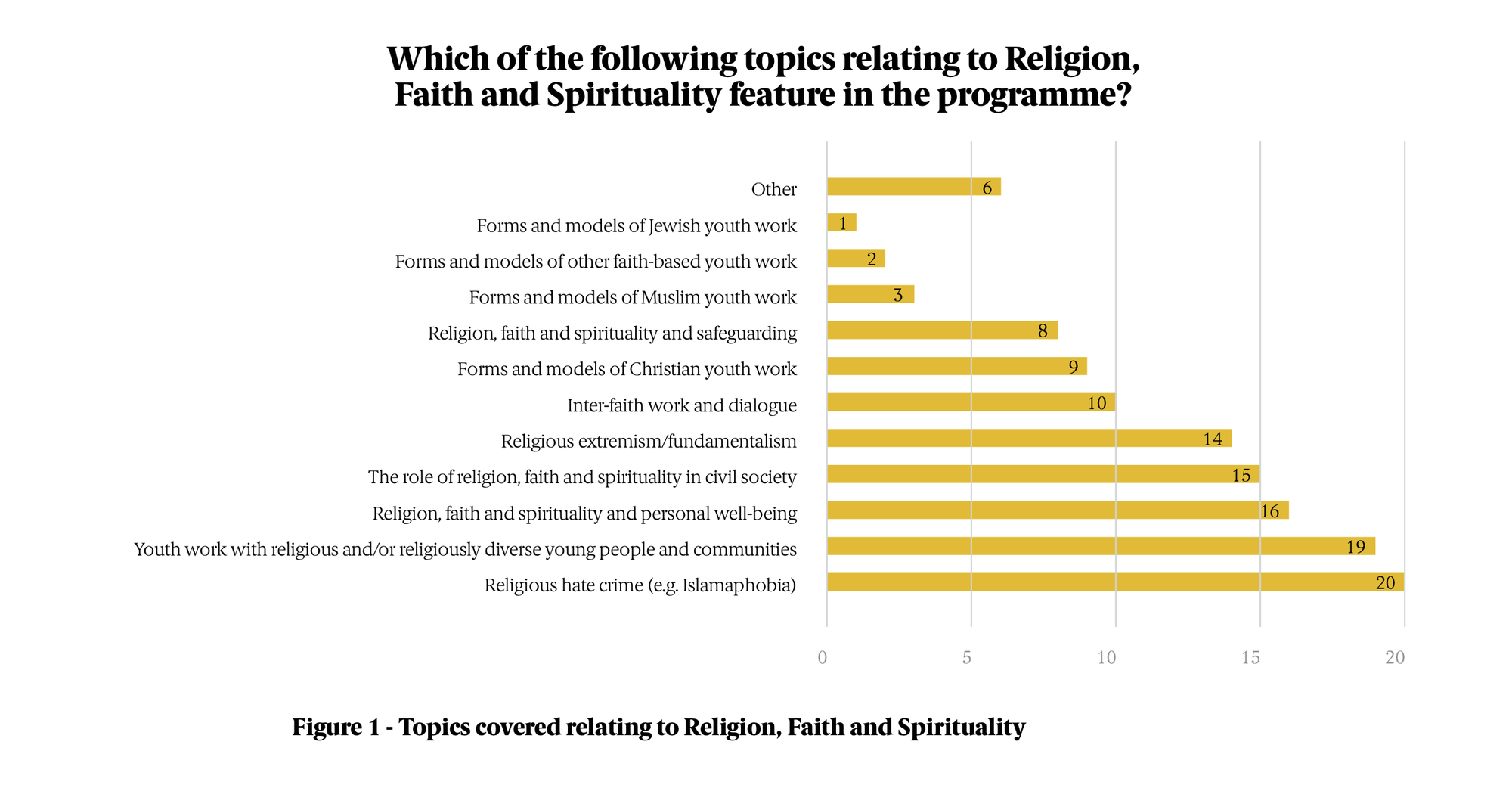

Christianity and Islam are the religions covered most frequently in youth work courses – with disproportionate negative representation in explicit coverage on secular programmes.

- The relevant topic most likely to be covered is religious hate crime, but courses are least likely to cover forms and models of specific faith-based youth work (e.g. Jewish, Muslim). Negative framings of Islam (at the poles of victim and perpetrator) are high in this regard, while coverage of Muslim youth work is low.

- The second topic most likely to be covered is youth work with religious/religiously diverse young people and communities. While this is encouraging, there is clearly scope to highlight what faith-based youth work looks like in specific religious contexts.

- The religions most likely to feature in training are Christianity and Islam.

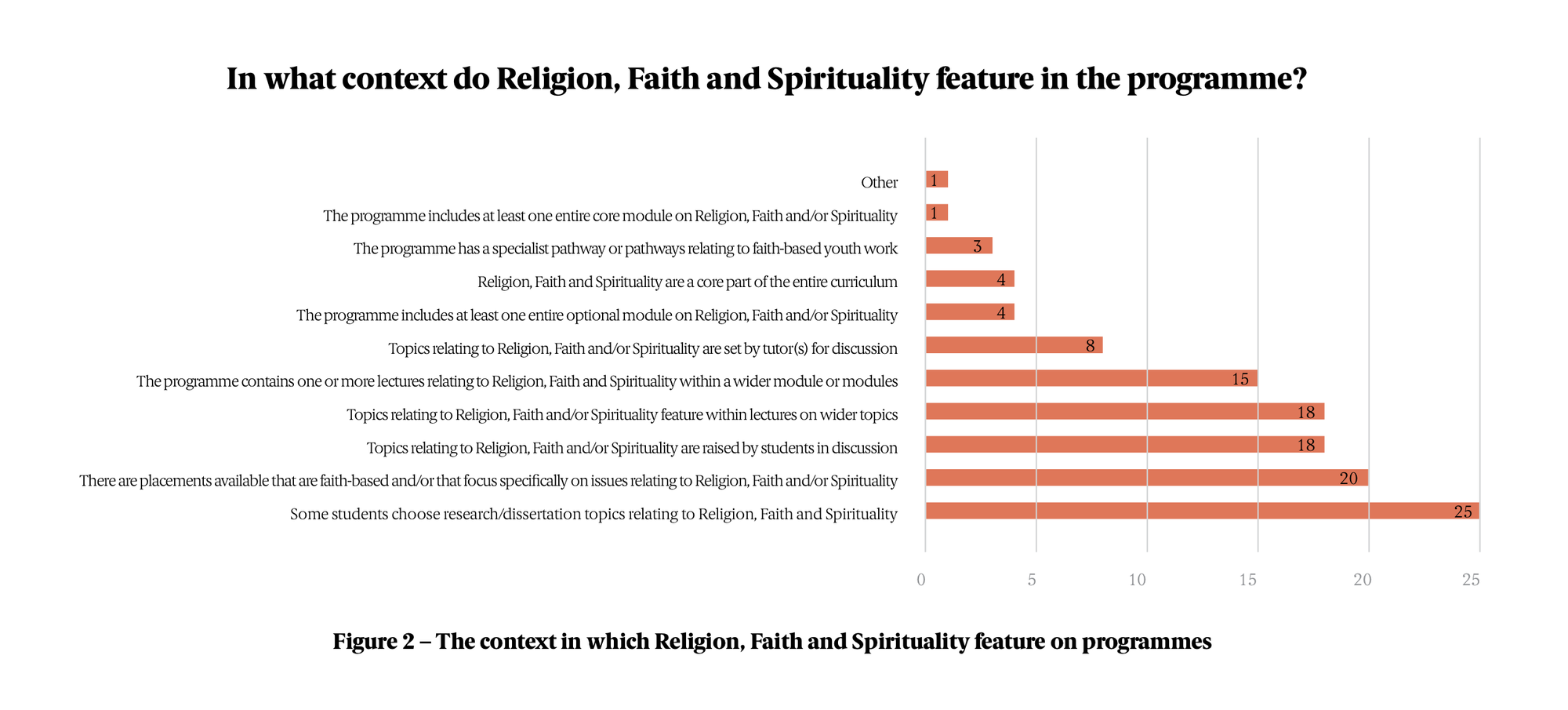

Where they feature, religion, faith and spirituality tend to be covered as part of broader teaching on social justice and anti-oppressive practice, but not as core modules.

- Over half of secular programmes had some ad hoc lectures and/or reference to religion, faith and spirituality during lectures on broader topics, but none identified it as a core part of the curriculum or had a core module on this.

- Nevertheless, many course leaders felt that religion, faith and spirituality were covered in broader modules on social justice.

“Values and beliefs encompass faith and spirituality, but not exclusively and we interpret this more widely in terms of Anti-Oppressive Practice, Social Justice etc. In addition, we ask students to engage with the politics of everyday life, and because of our location we have a number of students from different faiths – most often Christian and Muslim.”

Unlike other aspects of identity, religion, faith and spirituality are covered more through discussion and personal reflection than as core content or formal teaching.

- Most course leaders told us that the NOS were met through students reflecting on their personal beliefs, experiences and backgrounds, rather than religion, faith and spirituality being presented more broadly, or as core topics.

- The contexts in which religion, faith and spirituality are most likely to feature are students covering these issues in their dissertation topics and participating in placements that are faith-based.

- Discussion and dialogue are prioritised as learning contexts for religion, faith and spirituality on youth work courses, though course leaders reflected that this is not always comfortable for everyone, and that critique is an essential part of such dialogue.

- Two thirds of course leaders (66.7%) reported that they thought students from religious backgrounds felt either comfortable or very comfortable discussing their faith in group settings on the programme, with a third reporting either that students felt uncomfortable, or very uncomfortable, or that they didn’t know how they felt.

What does this mean?

The specific issue of religion, faith and spirituality appears to be neglected across secular programmes, not included in core curriculum content, and rarely presented as an option or specialism, meaning that engagement with it is not compulsory for trainee youth workers. Arguably, optional modules and ad hoc lectures are not sufficient to ensure all youth workers, regardless of their personal faith position, are equipped to understand and work with young people and professionals from diverse backgrounds. Where it is more explicitly covered, there is a risk that there is a disproportionately negative focus on issues such as hate crime, exclusion and radicalisation, largely in relation to Islam.

The place of religion, faith and spirituality as part of students’ critical dialogue and reflection was highlighted across programmes, facilitated at least to an extent by programme staff. While this is encouraging, a lack of explicit teaching on religion, faith and spirituality (to feed into such discussions) risks leaving student engagement with these topics to chance, leaving some experiences unheard and some problematic views and assumptions from those with or without religious beliefs going unchallenged.

"You have given me pause for thought about the extent to which we include discussions about this important issue as I do not believe our graduates are adequately prepared to engage with young people about religion and spirituality.”

Furthermore, if some students don’t feel comfortable discussing faith it may be unrealistic to expect discussion of personal values and beliefs to emerge naturally. At the very least, it puts more emphasis on the skills of course leaders, to overcome potential discomfort if it is likely to be a barrier to students sharing freely.

Overall, this research raises questions about how youth workers with JNC-recognised qualifications might be better equipped by their university training programmes to work with diverse religious communities and with the faith-based sector. Youth workers need to develop a religious literacy (Dinham, 2018) to work with the largest sector of their field and with the diverse religious young people who they will engage in their practice. A broader and more explicit recognition of religion, faith and spirituality, as well of other specific social justice issues and how these intersect in the youth work NOS, would support this.

We're grateful for the support of the following organisations