For young people struggling with their mental health, professional, external help won’t always be sought. Gry Apeland explores recent research into ‘self-care’ practices and the reasons for their appeal.

There are many reasons why young people might not seek or receive professional help when struggling with mental health difficulties, such as fear of stigma and lack of resources in mental health services. As such it is important to think about whether there are ways of coping with, or even improving, one’s mental health without the use of such specialised services.

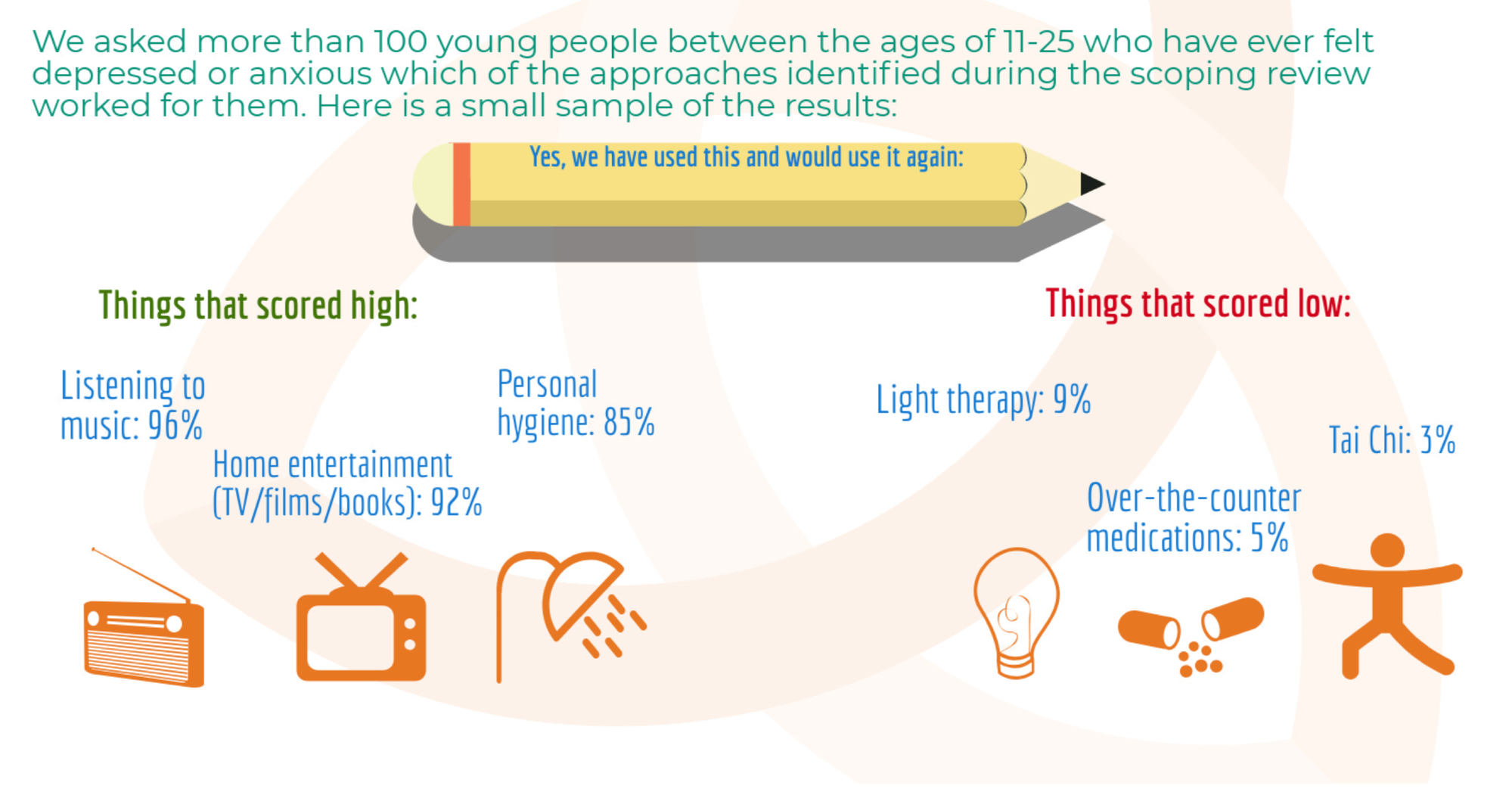

In response to this, the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families led online consultations and collaborations with young people over the autumn and winter of 2018/2019, looking at self or community approaches to addressing mental health. In particular they were interested in approaches to self-care that young people (aged 11-25) might be using in response to anxiety and depression. The consultations presented young people, and their parents or carers, with 85 different self-care approaches, and asked whether they had used them, whether they felt that they worked, and whether they would recommend them to others. They were also interested in why the young people chose a certain approach, why they thought certain ones were effective for them and avenues for future research.

The self-care study

156 participants took part in the study, of which 52% were aged 20-25, 30% were aged 15-19 and 8% were 11-14. Half (51%) of the participants reported a diagnosis of depression or anxiety. The majority of the participants identified as female (74%) and 70% were White British.

The self-care approaches appearing most often across all age groups, were listening to music, watching TV or films and reading a book. 11-14 year olds tended to mention spending time alone, drawing and painting most often, whereas 15-19 year olds rated using humour or laughing highly. 20-25 year olds mentioned talking to someone they trusted most often. Although there was a lot of similarities between the self-care approaches chosen by girls and boys, girls tended to prefer crying as a self-care strategy, whereas boys preferred humour and laughing over talking to someone they trusted.

When asking what was important to young people when choosing a self-care approach, the themes identified were: different things are important in different circumstances; having the freedom to choose an approach that’s right for me; that the approach works well; having the support of others; that the approach is accessible to me where I am; that the approach feels manageable and comfortable; how other people might perceive it, and not putting stress or burden on others.

Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families – self-care survey results:

The limits of self-care?

When asked why the young people thought these specific approaches were working for them, the themes identified were: I choose them myself and I know what has helped before; self-care approaches don’t always help; they distract from problems or difficult feelings; I feel supported; I can be alone; they help me to regulate emotions or let off steam; it’s a routine; they help me understand or express thoughts and feelings; there is no pressure.

Parents and carers were also asked what they thought about the various self-care approaches, and whether they would recommend them to others. While there were areas of consensus between the perceptions of parents and carers and the young people, some parents also described the limits of self-care approaches:

“I’m not sure they do work. We tried everything. There is too much emphasis on resilience building while austerity and school testing is damaging our children. A child died by suicide at my child’s grammar school but charities ignore the effects of 11+ testing, SATS, etc. You need to help to remove/reduce these stressors, don’t just treat the symptomology.”

This might highlight a challenge for the broader self-care culture. Although it is important to build resilience in young people and teach them about helpful self-care approaches, we cannot do it in isolation from also fighting for systemic changes that might positively benefit young people and their future. In the meantime, despite not commenting on the objective effectiveness of self-care approaches, this report highlights the perceived value of some self-care strategies, a subject that is always worth exploring with the young people you work with.